Geologic History of the

Mono Lake Region

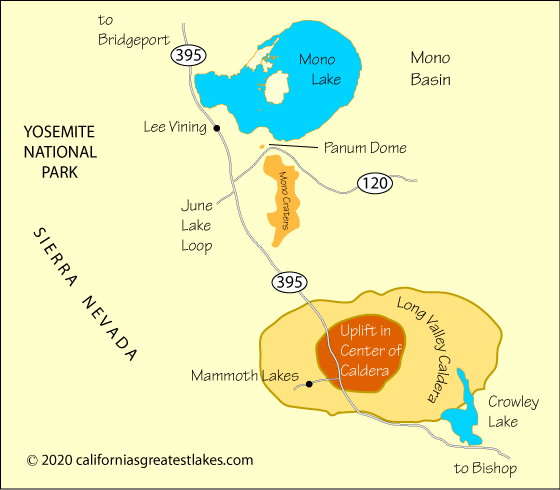

Mono Lake is located north of the Long Valley Caldera, a 20-mile long depression that is the aftermath of a volcano that erupted 760,000 years ago. In a massive explosion the volcano sent huge volumes of earth and ash into the sky and buried the surrounding area in hundreds of feet of volcanic debris. As a result of the eruption, the land collapsed, creating a 200 square mile depression known today as the Long Valley Caldera. Mono Lake formed soon afterward.

The area remains active, evidenced by numerous hot springs and frequent earthquakes. Mono Lake is part of the Mono Craters Chain, a 40,000-year-old series of plug-dome volcanoes. Plug domes are created when volcanic vents cool and the lava hardens to create a cap over the vent. Remnants of these volcanic vents are found throughout the Mono Basin. Signs of volcanic activity at Mono Lake are seen at Black Point and the Negit Islands. Panum Dome, just south of Mono Lake was formed about 600 years ago. More recent eruptions occurred in Mono Lake between the mid-1700s and the mid-1800s.

A period of ongoing geologic unrest in the Long Valley area began in 1978, when a magnitude 5.4 earthquake struck 6 miles southeast of the caldera. The area has since experienced numerous swarms of earthquakes, especially in the southern part of the caldera and the adjacent Sierra Nevada.

Recent History of Mono Lake's Water

Water from Mono Lake's tributaries was first diverted to Los Angeles in 1941. By 1962 the lake's level had dropped almost 25 feet. As water levels fell, the salinity increased, drastically changing the ecology of the lake. Algae and shrimp began to die off and nesting islands became peninsulas, exposing them to predators. By 1995 the lake was 40 feet below its former level. Tributaries were mere trickles and dust storms swirled in the Mono Basin.

In 1978 David Gaines and others formed the Mono Lake Committee which began to campaign to save the lake from devastation. Others joined the battle to rescue the lake, including the Audubon Society and California Trout. Through litigation and with the support of the California State Water Resources Control Board, a restoration plan was approved to bring the lake back to a reasonable level.

Los Angeles continues to divert water, but the amounts are strictly limited. When the lake level falls below an elevation of 6,377 feet then no water may be diverted. Minimum flows are specified for tributaries such as Lee Vining Creek, Walker Creek, Parker Creek, and Rush Creek. When the lake stabilizes at 6,391 feet then new restrictions will be put in place to help it maintain a range close to that level.